- Introduction

The dictionary defines ‘Vocation’ as ‘career’, ‘calling’, or the particular occupation for which you are trained. so, as a research scholar what one should keep in mind? what are the differences between Scholar and Critic? How one should move from critic to scholar? All these points he is discussing in the very beginning of the present chapter. So, in a sense, the present chapter by Richard D. Altick is grounding for the research scholar.

Altick begins this chapter by quoting the words of Howard Mumford Jones –

Our business, as I understand it, is to find out in a humble spirit of inquiry what literary masterpieces really say

In the beginning, he differentiates between Scholar and critic. He says, as such, we all are dedicated to the same task, the discovery of Truth. He writes that the critic’s business is primarily with the literary work itself – with its structure, style, and content of ideas. The scholar, on the other hand, is more concerned with the facts attending its genesis and subsequent history.

He writes Literary research is devoted to the enlightenment of criticism. It seeks to illuminate the work of art as it really is. Equally, it tries to see the writer as he really was, his cultural heritage and the people for whom he wrote as they really were.

Altick was visionary that, even in the 1960s he was able to see the danger of connecting publication with the promotion in institutions. Because this is very much dangerous thing which affects the ability of teaching. Some teacher may keep on publishing so many research papers and attend many conferences and seminars but may not teach in class at all. Whereas some very good teacher who does excellent teaching, who may not publish so much are at loss.

In the present chapter Altick discusses the literary journey. A journey of Critic to a researcher to Scholar. The critic is attached to the text whereas the scholar should be detached from text. Research is an occupation but scholarship is a habit of mind or a way of life. Altick questions that what are the chief qualities of mind and temperament that go to make up a successful and happy scholar?

Subsequently, he answers that the ideally equipped literary scholar should have come to his profession after serving a practical apprenticeship in one or the other of two occupations: law and journalism. One may ask why did he emphasize more on these two professions? Because he argues, the practice of law requires a thorough command of the principles of evidence, a knowledge of how to make one’s efficient way through the accumulated “literature” on a subject and a devotion both to accuracy and to detail. Journalism, more specifically the work of the investigative reporter, also calls for resourcefulness – knowing where to go for one’s information and how to obtain it, the ability to recognize and follow up leads, and tenacity in pursuit of the facts. Both professions, moreover, require organizational skill, the ability to put facts together in a pattern that is clear and, if the controversy is involved, persuasive

According to Altick, the ideal researcher must love literature for its own sake. He must be an insatiable reader. the researcher must have a vivid sense of history: the ability to cast himself back into another age. He must be able to readjust his intellectual sights and imaginative responses to the systems of thought and the social and cultural atmosphere that prevailed in fourteenth-century England or early twentieth-century America. He must be able to think as people thought when Newton was educating them in the laws of physics and to dream like people. Otherwise, he cannot comprehend the current attitudes or the artistic assumptions that guided an author as he set pen to paper. dreamed when Byron was spinning out his Oriental romances. Before understanding a certain period in history, he must know about historical, social, political circumstances of that time. So that he may understand the time in a better way. Newton had faced so many problems and threats from the contemporary authority in convincing them about his scientific inventions. It is now that we can understand his views easily but at that time it was nearly impossible to convince the people. So, when a researcher studies about him, he should keep in mind that period and study accordingly. At the same time, he must retain his footing in the twentieth century for the sake of the indispensable perspective the historian needs. His sense of past, then, must be a double vision – intimate and penetrating and yet detached

Literary scholarship tolerates to a degree the subjective impression, as is inevitable in a discipline that deals with the human consciousness and the art it produces. But as an assembler and assayer of historical facts, a literary scholar needs to be as rigorous in his method as a scientist. Background in science can be good preparation for the science because the same qualities are required in both like : intellectual curiosity, shrewdness, precision, imagination – the lively the inventiveness that constantly suggests new hypotheses, new strategies, new sources of information, and, when all the data are in, makes possible their accurate interpretation and evaluation

Scholarship involves a great amount of detail work, in which no margin of error is allowed. It is no occupation for the impatient or the careless; nor is it one for the easily fatigued. A scholar must not only be capable of hard, often totally result in less work – he must actually relish it

Altick writes that “Learning without wisdom is a load of books on an ass’s back.” One can be a researcher, full of knowledge, without also being a scholar. He suggests a very thin line between researcher and scholar. Research is the means, scholarship the end; research is an occupation, the scholarship is a habit of mind and a way of life. A scholar is more than a researcher, for while he may be gifted in the discovery and assessment of facts, he is, besides, a man of broad and luminous learning. He has both the wisdom and the knowledge that enable him to put facts in their place

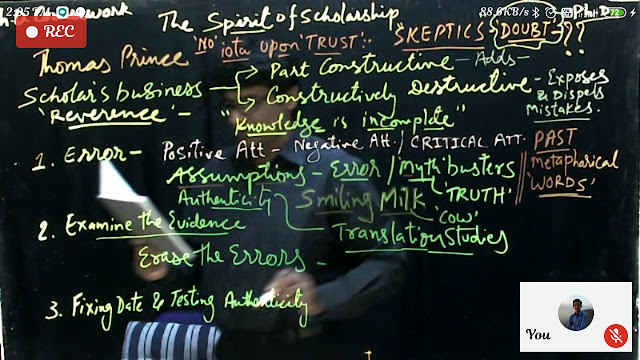

- The Spirit of Scholarship

After laying a foundation in the first chapter, he advances his views in the next chapter about the spirit of scholarship. Altick begins the chapter with the following quote.

“And as I would not take the least Iota upon Trust, if possible; I examin’d the Original Authors I could meet with: ... I think a The writer of Facts cannot be too critical: It is Exactness I aim at, and would not have the least Mistake if possible, pass to the World”.

– Thomas Prince

He very clearly says that the Researcher should nor Trust / believe anything easily without examining it. Even if the author himself comes and says that this is the meaning of my words/texts, then even doubt it. It may happen that a writer may have changed his views because of some kind of pressure or protest against him. So, the researcher should doubt everything. This should be his habit of mind.

The essay is divided into three parts.

1. Error: Its Prevalence, Progress, and Persistence

2. Examining the Evidence

3. Two Applications of the Critical Spirit: Fixing Dates and Testing Genuineness

The scholar’s business is in part constructive and in part constructively destructive. It means that he has to do a critical analysis of literary texts and add more knowledge in the field, at the same time he has to show mistakes as well of writer and text.

In the first part of the essay, he notes that Criticism conducted in the shadow of error is criticism wasted. He may be a trusting person in his personal life but in his professional life as a Scholar, he must cultivate a low opinion of the human capacity for truth and accuracy. A scholar should be thoroughly sceptic. Everything is held open for question. Doubt and question everything before believing it.

Altick accepts that all humans are fallible. Knowingly or unknowingly we tend to make mistakes. So, we have to reconcile ourselves to a small, irreducible margin of error in our work. But fatalism cannot under any circumstances rationalize carelessness. The researcher can’t blame destiny for the mistakes in his work. Granted that perfection is beyond our reach, we must devote every ounce of resolution and care to eliminating all the mistakes we can possibly detect.

He advises scholars to choose the most dependable text. Because there are many editions of texts are available. It may happen that the editor may have changed something which was not in the original menu script. Or subsequent editions may be totally different than the earlier versions. Sometimes new words, phrases or even entire chapters are added or deleted. Sometimes print and pdf copy may have a lot of variations. So, one should be very careful in choosing the authentic texts. To prove his point, he gives many examples from English literary history. an edition contains an elaborate apparatus of footnotes and textual variants are no absolute guarantee that the text is indeed accurate. There is a possibility of printing error also.

As a result, it becomes very important for the scholar to examine all evidence properly to rectify the mistakes that occurred in the process of historical transmission. Author’s autobiographical narrative can be important but we should never accept them at their face value. Apart from their frequent unreliability as to specific dates, places, and other historical facts, they usually are idealized, embroidered through the artistic imagination, coloured by the desire for self-justification

Scholar’s task is even more difficult when several versions of the same story are available. it is not usually possible for a scholar to say with absolute confidence that this, and this alone, is what happened in a given episode; the best he can do is assert that everything considered, the probabilities favour one set of details more than another

Altick says the problem of evaluating primary evidence is complicated when several first-hand witnesses, all presumably of the same dependability, differ among themselves. And to prove his point he gives an example of Wordsworth that how various contemporary portrayed him vividly. So, it becomes difficult for a scholar to find out which one to believe. He adds that the source of every statement has to be analysed in view of the character, reliability, temperamental sympathy, and possible bias of the contributor.

In the third part of the essay he says very precisely that Be sure of your facts – and if in the slightest doubt, take another look

scholars must take particular care to cultivate an acute awareness of time. By applying our sharp time-sense to the documents and received narratives before us, we can often place an event more precisely in the sequence to which it belongs, and even more important, we may thereby prove or disprove a doubtful statement. Chronological considerations sometimes may lead us into deeper waters than we anticipate

He concludes his chapter by saying that All that glitters is not gold and alerts to research scholar to the possibility that a manuscript or book he is examining was produced with deceptive, if not clearly criminal, intent. The date may be erroneous; the document’s handwriting may not be that of the putative author; a “new edition” of a book may contain a text that has been reprinted without change or, on the other hand, has been silently abridged. So, one should be very careful in all these things and perhaps, in the true sense that is the Spirit of Scholarship

Works Cited

Altick, Richard. The Art of Literary Research. 4. New York: W.W. NORTON & COMPANY, INC, 1975. pdf.

No comments:

Post a Comment